Research examines how stroke patients regain walking, balance function

Following a stroke, many people have issues with walking and balance. Physical therapy can help patients recover, but most people will plateau around six months after their stroke.

Patients with better outcomes develop what is called post-stroke sensory reweighting (PSR), the process of the senses coming back and in better equilibrium to improve walking and balance.

A new University of Cincinnati study, funded by a $445,000 Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant, is examining how exactly patients develop PSR during the first six months of recovery.

Oluwole Awosika, MD.

Principal investigator Oluwole Awosika, MD, said our ability to walk and balance is aided by components that include proprioception (the body’s ability to sense movement and action), the vestibular system (which includes inner ear function and helps maintain balance), posture and vision. When one of these components is compromised or weakened, the other senses are heightened to make up for the deficit.

“Imagine someone who’s trying to do a difficult yoga pose on one leg,” said Awosika, associate professor in the Department of Neurology & Rehabilitation Medicine in UC’s College of Medicine and a UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute physician. “One trick is to fixate your eyes on a particular target. You don’t really have proprioception as well because you’re using only one limb, but you’re using your eyes to fixate and balance.”

Following a stroke, the equilibrium of this system of senses is impaired or lost, which may explain the severe walking and balance issues experienced immediately during the early stages after stroke. Moving forward, the scope of each individual’s recovery is largely determined by the development or lack of development of PSR.

“People who have successfully developed PSR will still be unstable but will be able to maintain balance and not fall as much, whereas those that do not have sensory reweighting will have a higher risk for fall, will walk slower and will also have walking asymmetry,” Awosika said. ”Not having PSR severely impacts one’s outcome, and it’s a drastic difference between those that can and cannot.”

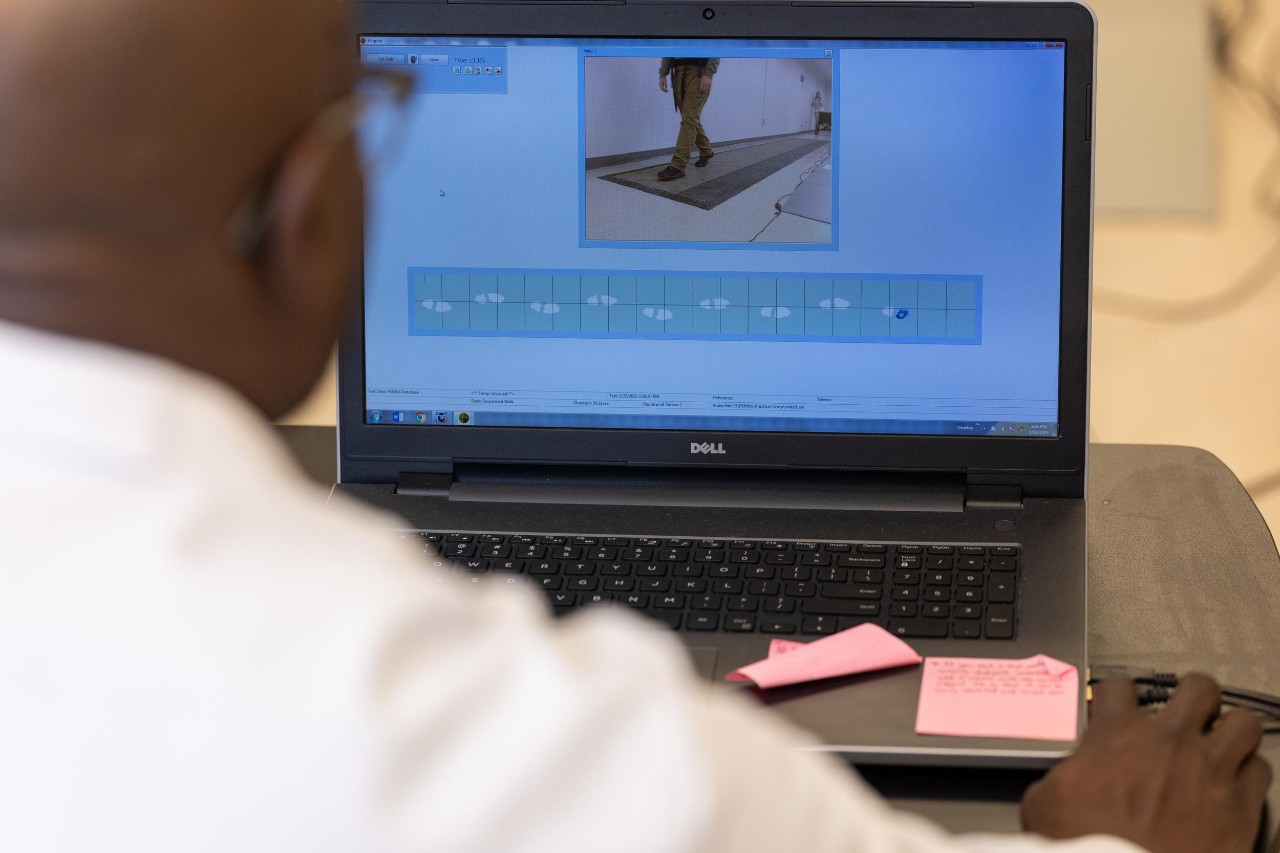

The posturography machine takes patients through four different phases of testing, and Awosika said future studies could be targeted based on specific posturography signatures.

Researchers do not know much about how PSR develops within patients, and why in some patients and not others, so this study will look at what is happening in patients’ sensory systems over the six months following their stroke.

To accomplish this, they’ll use a tool and technique called posturography, which measures which senses involved with walking and balance are strong and which are impaired as patients go through four different conditions of testing.

“Anyone not able to complete any of the four conditions of posturography is considered PSR-negative,” Awosika said. “Each person’s different, so using this tool we can know if it is the vestibular system that’s most impaired or strongest, the proprioception or vision.”

The team will use posturography to measure patients at two, four and six months following their stroke. They will also collect baseline imaging and demographic information to look for patterns that predict whether a patient will develop PSR.

“If we’re able to determine how this evolves, we can then determine what structural conditions may lead to a particular pattern developing,” Awosika said.

The plan is to enroll a total of 40 patients who had an ischemic stroke in the study over two years.

Using posturography data to diagnose what senses are strongest could help personalize rehabilitation plans for patients.

Goals and potential applications

Learning how PSR develops could open the door for future studies that target interventions based on an individual patient’s posturography signature, Awosika said. Researchers may also be able to improve trial designs by randomizing patients based on PSR status and/or setting up separate studies for PSR-negative patients.

“Sometimes an intervention seems promising, but we don’t really have a good way of selecting who comes into the study, and the results end up becoming equivocal or negative,” he said. “Incorporating PSR status and development could inform and make clinical trials better designed.”

Awosika added that current inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient therapy practices are usually one size fits all, but knowing which senses are stronger and weaker can help customize therapy plans to each individual based on their needs.

“Posturography devices are actually present in some therapy gyms as a tool to train with, but not to diagnose,” Awosika said. “So if we know which sensation is strongest, maybe you can actually make it even stronger to compensate. Or maybe it’s possible to actually strengthen the weaker senses.”

Innovation Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1R21HD115776-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Featured photo at top of Awosika observing a person using the posturography machine. All photos/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand.

Latest UC News

- Black FUTURE month underway with something for allGet ready for a month full of celebrations, from galas to thought-provoking conversations to delicious food! Black FUTURE Month, sponsored through UC’s College of Arts and Sciences, is underway to observe Black History Month.

- CCM Summer presents Film Scoring Summit for high school studentsDo you have a favorite film music theme? Have you ever wondered how film scores come to life? Discover the art of film scoring during the one-day Film Scoring Summit at UC's College-Conservatory of Music (CCM). Led by Professor Jasmine Guo, the Film Scoring Summit is a free event for rising 10th-12th grade students. Participants will delve into the magic of music in film, experiment with scoring and learn about CCM's Commercial Music Production (CMP) program. The Summit ends with a tour of CCM's recording studios and a Q&A session with faculty.

- Experts: Sports betting up, but so is problem gamblingThe University of Cincinnati and UC Health Lindner Center of HOPE's Chris Tuell spoke with WLWT about the risk and apparent rise in sports gambling addiction.

- Travis Kelce and Bryan Cook take center stage at Super Bowl LIXTight end Travis Kelce and safety Bryan Cook took center stage for the Kansas City Chiefs in Super Bowl LIX at Caesars Superdome at Super Bowl Opening Night on Monday.

- Digital art therapy application designed to improve mood in AYA brain cancer survivorsThe UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center will lead a study using a new art therapy application designed in collaboration with University of Cincinnati experts for patients ages 18-24 (AYA) brain tumor survivors.

- Atmospheric scientist follows her passion to global extremesJulianne Fernandez parlayed her experience as a University of Cincinnati geosciences student into a career that has taken her to the bottom of the world and thousands of feet beneath its surface.