Mosquitoes can be extra-bitey in droughts

Mosquitoes are able to survive prolonged droughts by drinking blood, which helps to explain how their populations quickly rebound when it finally rains, biologists at the University of Cincinnati said.

UC postdoctoral researcher Christopher Holmes led a study examining how two species of mosquito known for infecting people with diseases such as malaria were able to survive nearly three weeks without rain.

The findings could help explain why the incidence of infection from mosquito-borne illness does not always decline during droughts. While there may be fewer mosquitoes, those that survive bite more often.

“We’re finding that mosquitoes bite people more than we imagined, unfortunately,” Holmes said.

And mosquitoes appear to be benefiting from climate change as winters get warmer, Holmes said.

The study was published in the journal iScience.

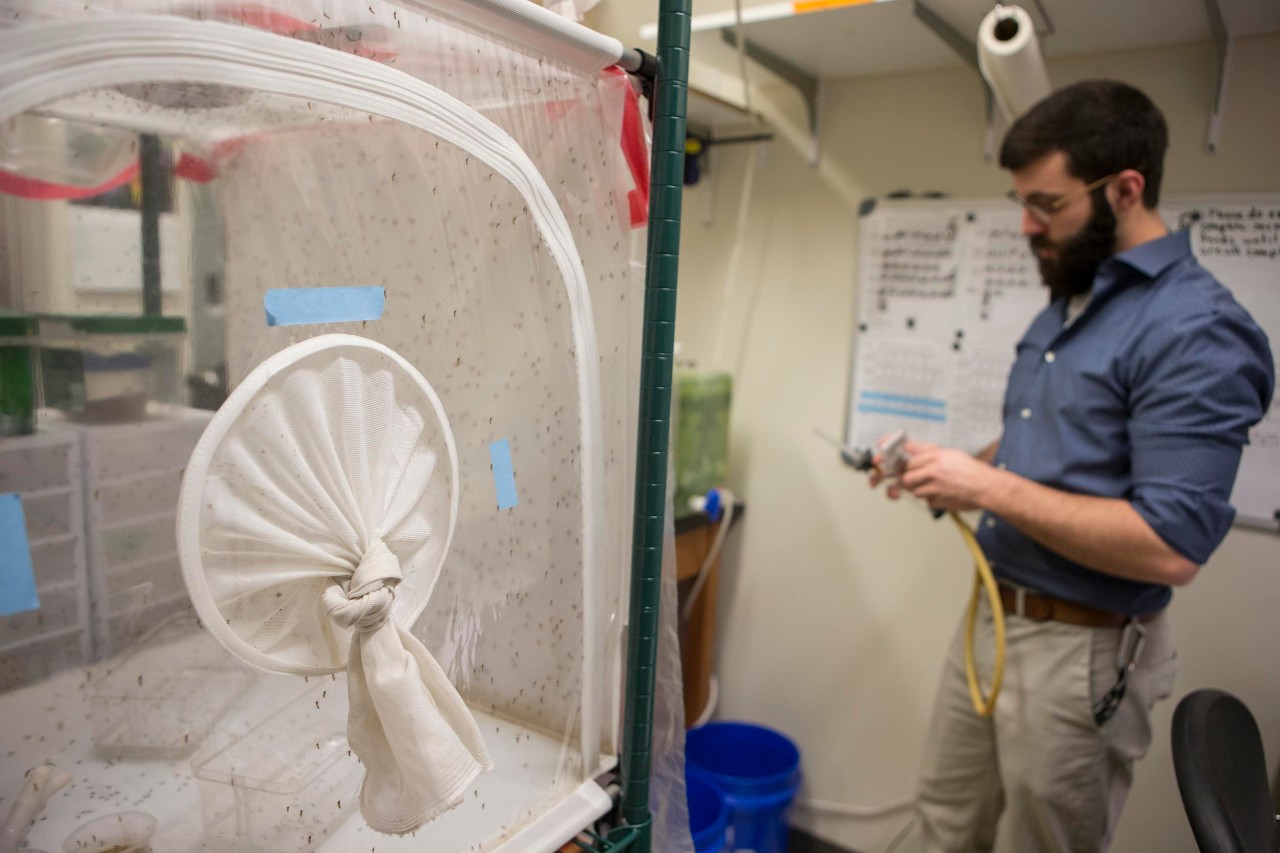

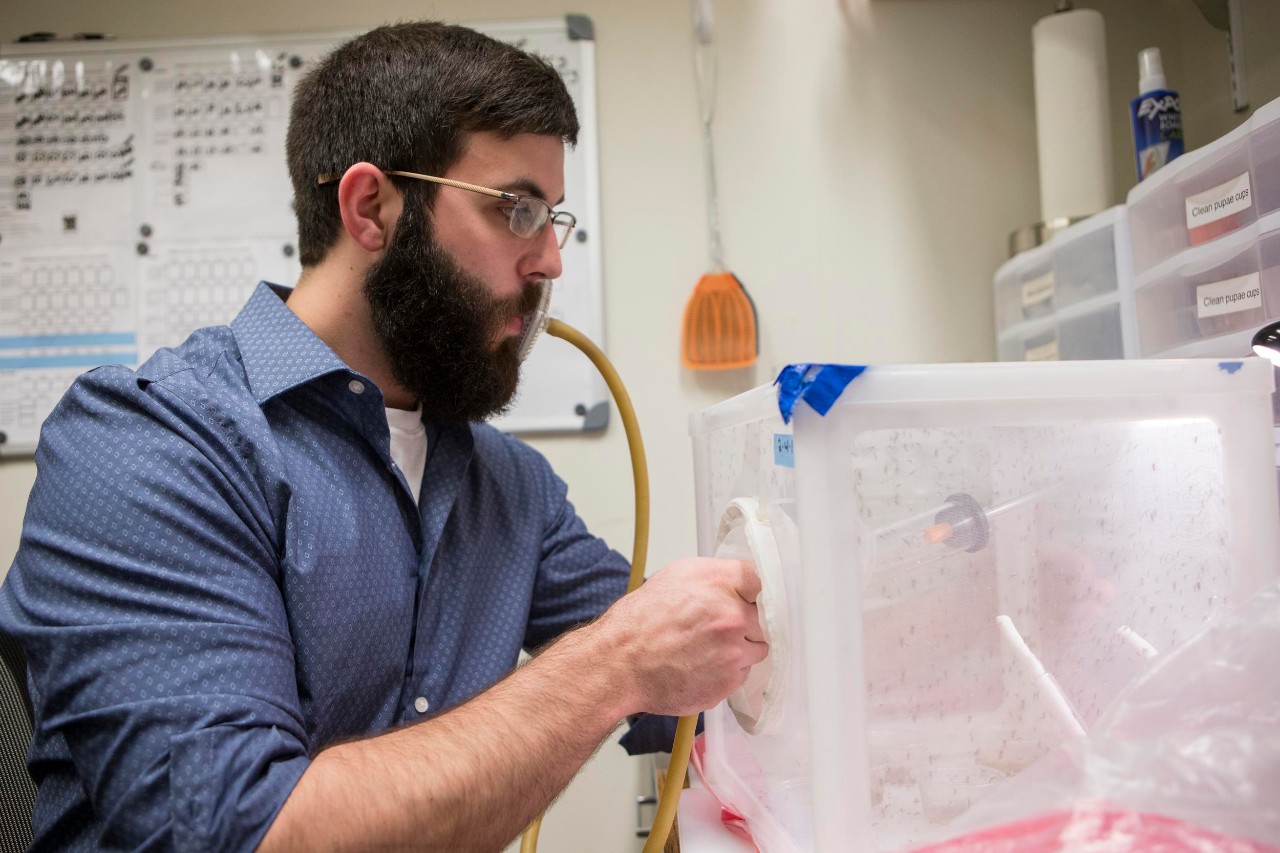

UC postdoctoral researcher Christopher Holmes works with mosquitoes in a biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Holmes said under favorable conditions, female mosquitoes draw blood from a host to fuel egg production. About four days later, the mosquitoes lay their eggs and seek another blood meal to repeat the process.

But during droughts, mosquitoes will supplement their initial blood meal by feeding again and again to stay hydrated in the days before laying eggs. And this could give mosquitoes more opportunity to spread diseases like dengue fever, Zika or malaria, he said.

“Everyone is under the assumption that during drought there are fewer mosquitoes and less opportunity to spread mosquito-borne illness. But the modeling doesn’t necessarily show that,” co-author and UC Professor Joshua Benoit said.

Knowing more about mosquito biology is critical to understanding how they survive and reproduce.

Joshua Benoit, UC Professor of Biological Sciences

The study examined mosquitoes that were genetically altered to impair particular senses such as the ability to detect carbon dioxide, key to finding people or animals to bite. They also impaired some mosquitoes’ ability to sense changing humidity levels.

They found that carbon dioxide-impaired mosquitoes did not survive dry periods because they could not find hosts to bite.

“Carbon dioxide is one of the major drivers of feeding behavior. Even though the mosquitoes were hungry or thirsty or both, in the absence of being able to use carbon dioxide to find a host, they just died,” Holmes said.

Co-author and UC doctoral student Souvik Chakraborty said even the eggs of mosquitoes have impressive abilities to withstand long periods of drought.

“The Aedes aegypti mosquito is resistant to drying out. Its eggs can survive sometimes for as long as a year,” he said. “You’ll get rainfall and the water level rises and as soon as it touches the eggs, they hatch like magic.”

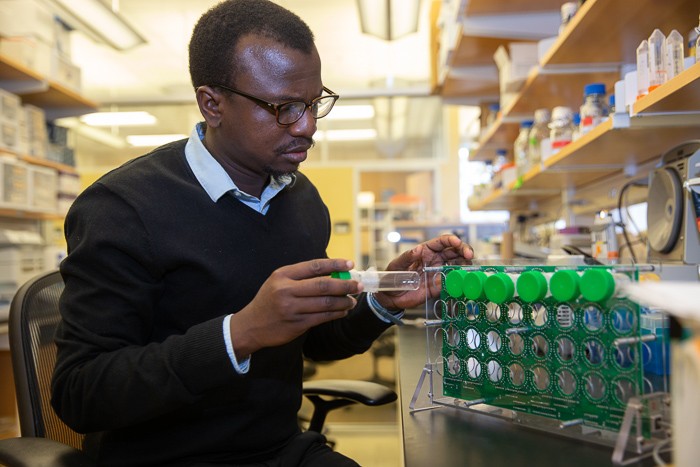

UC postdoctoral fellow Oluwaseun Ajayi works in a biology lab. He is coauthor of a new study examining how mosquitoes survive long periods of drought. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Likewise, UC postdoctoral fellow and study coauthor Oluwaseun Ajayi said mosquitoes such as the species Culex, which is found around the world, can tolerate cold temperatures, too.

“They have the ability to anticipate winter and quickly reduce their metabolism to overwinter for as long as five months,” he said.

“They’re often called a house mosquito,” Holmes added. “They’ll hide out in cellars or culverts. Before winter, they’ll drink nectar and get really fat, building up these huge lipid deposits. And then when it gets warm enough, they’ll quickly seek a blood meal, lay eggs and die.”

Lead researcher Holmes said the team’s latest findings give him a greater appreciation for the improbably long history of mosquitoes on Earth. The oldest mosquitoes date back to the early Cretaceous 125 million years ago. They are an integral part of the food chain, feeding everything from fish to birds to bats and other insects.

Today, the diseases they spread are responsible for killing more than 700,000 people each year.

“It speaks to the effective survival and reproductive strategies of mosquitoes,” Holmes said. “Some are stealthy and sneak up at you at night. Some are more aggressive, bite you and get out.”

Benoit said the study demonstrates the resilience of these insects that predate dinosaurs.

“They live almost everywhere except Antarctica. They tolerate a wide range of habitats,” he said. “Knowing more about mosquito biology is critical to understanding how they survive and reproduce.”

Featured image at top: UC postdoctoral fellow Christopher Holmes displays a vial of mosquitoes in UC Professor Joshua Benoit's biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

UC postdoctoral researcher Christopher Holmes uses an aspirator, or pooter, to collect a mosquito for study in a biology lab. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Latest Bicentennial News

- Reviving the dream: UC honors MLK with joyful celebrationsThrough gatherings, music and meaningful discussions, UC’s African American Cultural & Resource Center, UC Health and UC’s Center for Community Engagement invite the campus and broader community to honor the dream while charting a path toward a brighter tomorrow.

- Study examines blood vessels’ role in neuropathic spontaneous pain, potential treatmentsThe University of Cincinnati’s Jun-Ming Zhang has received a five-year, $3.1 million grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to research the effect of blood vessel movement inside sensory ganglia on neuropathic spontaneous pain.